A training mask is a good way to provide resistance to the diaphragm.

Breathing is a necessary automatic part of life that we don’t think much about. When we take a breath, muscles in our body assist our lungs expansion, drawing in air from around us. Our lungs extract the oxygen from the air and shuttle it to our muscles. Our muscles use oxygen to produce energy during work. With this simple understanding, it becomes immediately clear that more oxygen = more energy = more work.

Improving your breathing function is beneficial for anybody, not just an athlete, but the performance implications are huge. Postural dysfunctions from muscular imbalances can inhibit a person’s respiratory function over time! Often people with imbalances adapt to breathing with their secondary respiratory muscles such as the chest and neck. Relying on secondary respiratory muscles instead of the diaphragm will cause it to become weakened and dysfunctional. When your diaphragm is dysfunctional your lung capacity, among many other things suffers!

How we breathe

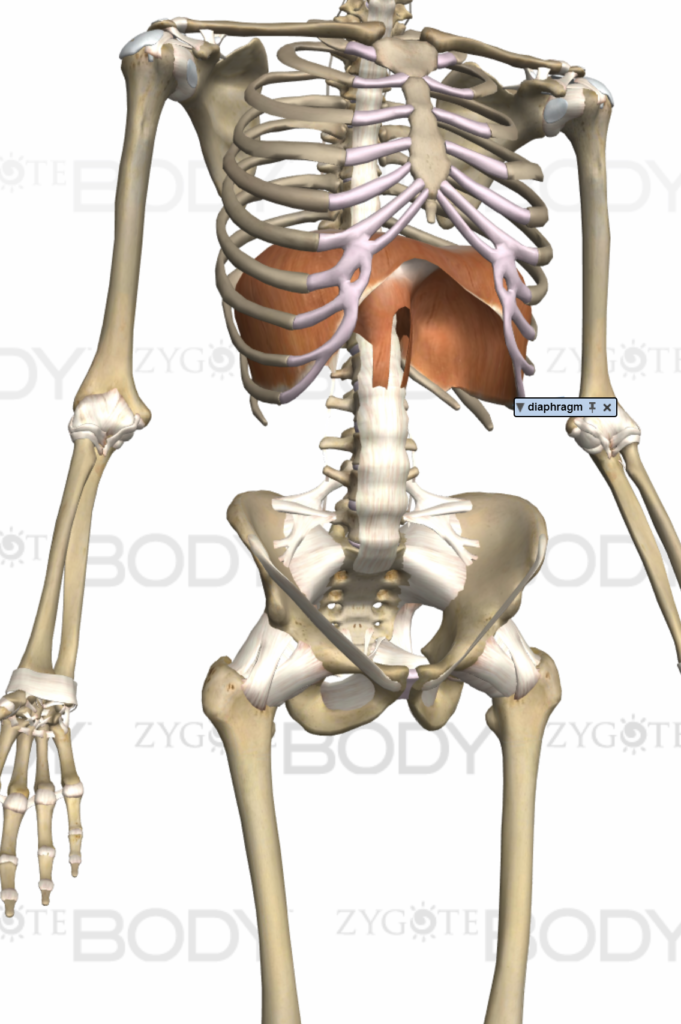

The diaphragm – your main respiratory muscle expands downward into your abdominal cavity allowing for maximum inhalation!

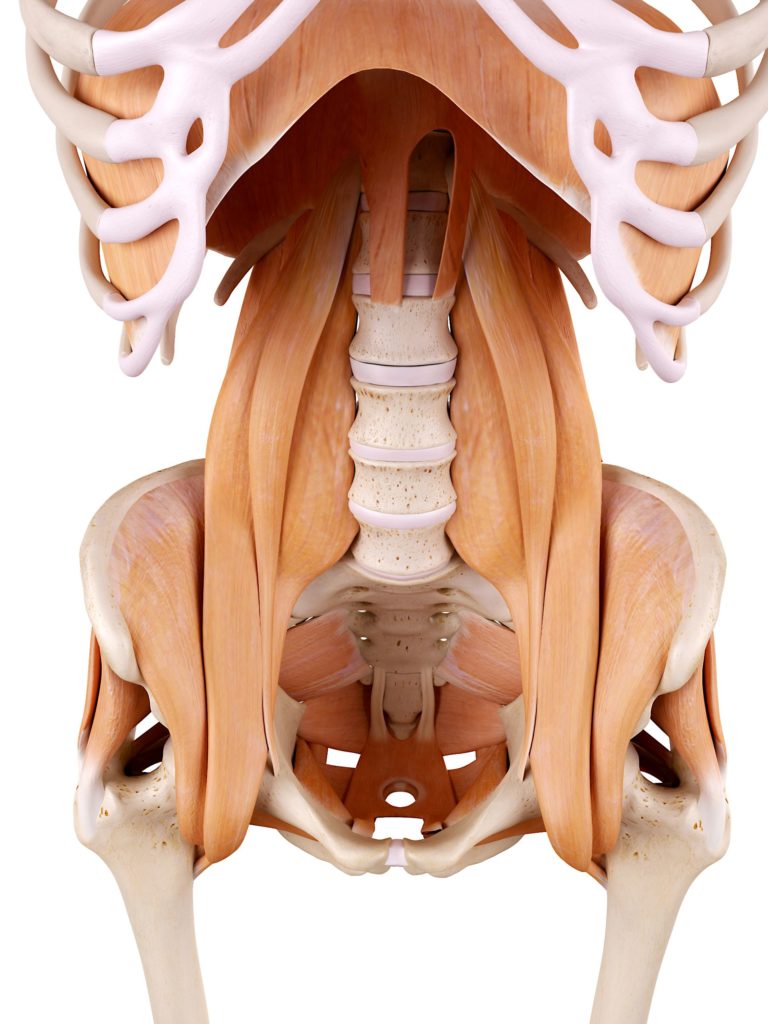

We use muscles to breathe, and optimally our diaphragm is our main respiratory muscle. Our diaphragm needs to expand down into our abdominal cavity in order to draw air into the lungs. The more room it has to expand downward, the bigger the breath! Our organs are pushed down into our pelvic floor when we take a huge diaphragmatic breath and this is where muscular imbalances might affect our ability to breathe fully. If our pelvic floor is not oriented properly due to dysfunctions such as lumbopelvic hip complex dysfunction (LPHCD) then there is a less downward expansion of the diaphragm and we get a shallower breath. Over time the inability of the diaphragm to expand fully into the abdominal cavity will create weakness and dysfunction of this muscle. When the diaphragm is dysfunctional we rely on our secondary respiratory muscles such as our chest and neck muscles.

Restoring function to your breath

In order to restore function to the diaphragm, we have to address both the dysfunction in the hips, the chest and the neck. Releasing and stretching muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid in the neck, levator scapularis in the back of the neck, and the pec minor in the chest could help keep these muscles relaxed during breathing. Many of the muscles associated with dysfunctions such as Forward Head Posture (FHP) and Upper Crossed Syndrome also contribute to these improper breathing patterns. Consulting the Corrective Exercises for these dysfunctions can provide the release techniques and stretches for these secondary respiratory muscles.

With healthy posture and a functioning core and pelvis, a strong diaphragmatic breath starts with the expansion of your lower belly and then up into your chest and ribs. A strong breath is circumferential, outward in all directions. Maintaining a slight tension in your core and glutes will keep your pelvic floor in line for optimal diaphragm expansion.

Often when the diaphragm is dysfunctional it becomes too weak to fully expand. You will notice these breaths come from the chest. A dysfunctional breath elevates the shoulder, raises and expands the chest and strains the neck. Often you will see people with poor cardiovascular health struggling to catch their breath by bending over, this is our bodies attempting to align our torso for a larger diaphragmatic breath!

Strengthening and improving diaphragm

Exercises such as 90/90 balloon breathing keep a person lying on their back, aiding optimal breathing position by helping to maintain proper core tension and abdomen expansion. The ground provides good feedback during the breath. Pushing your back into the ground while expanding your belly during your inhale is a helpful tip. Breathing into a balloon is a good way to provide resistance to the diaphragm. With a balloon, focus on inflating it evenly without taking your mouth off it. A small weighted object like a kettlebell or medicine ball can be placed on the belly to provide resistance to strengthen the diaphragm.

90/90 breathing: