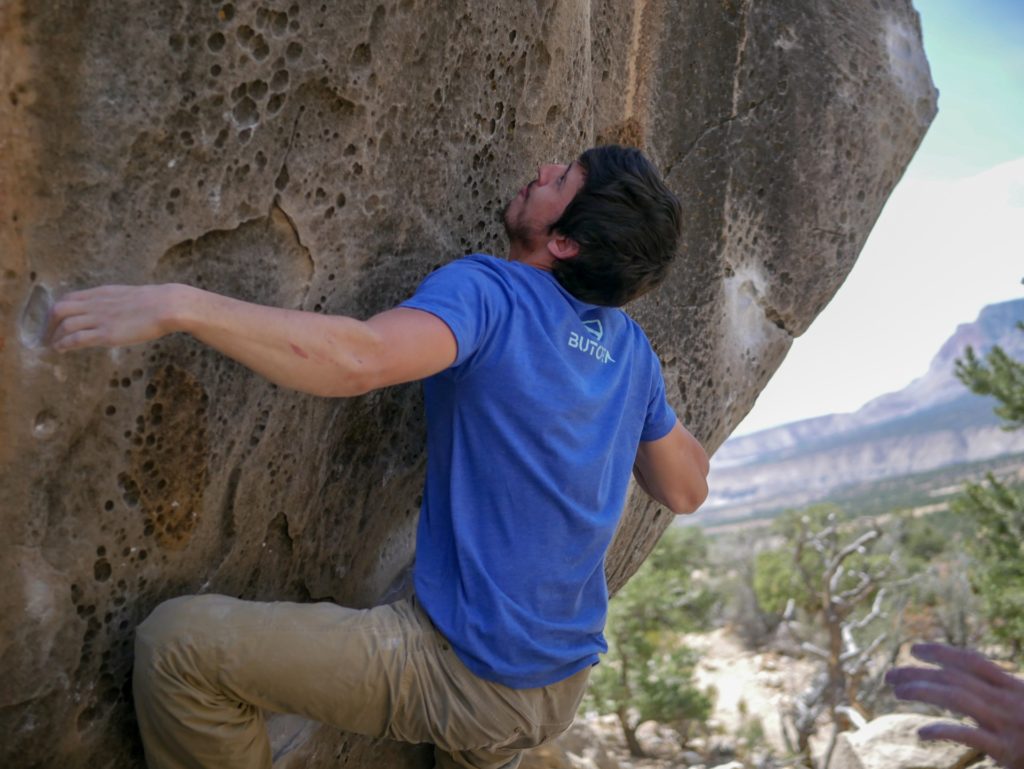

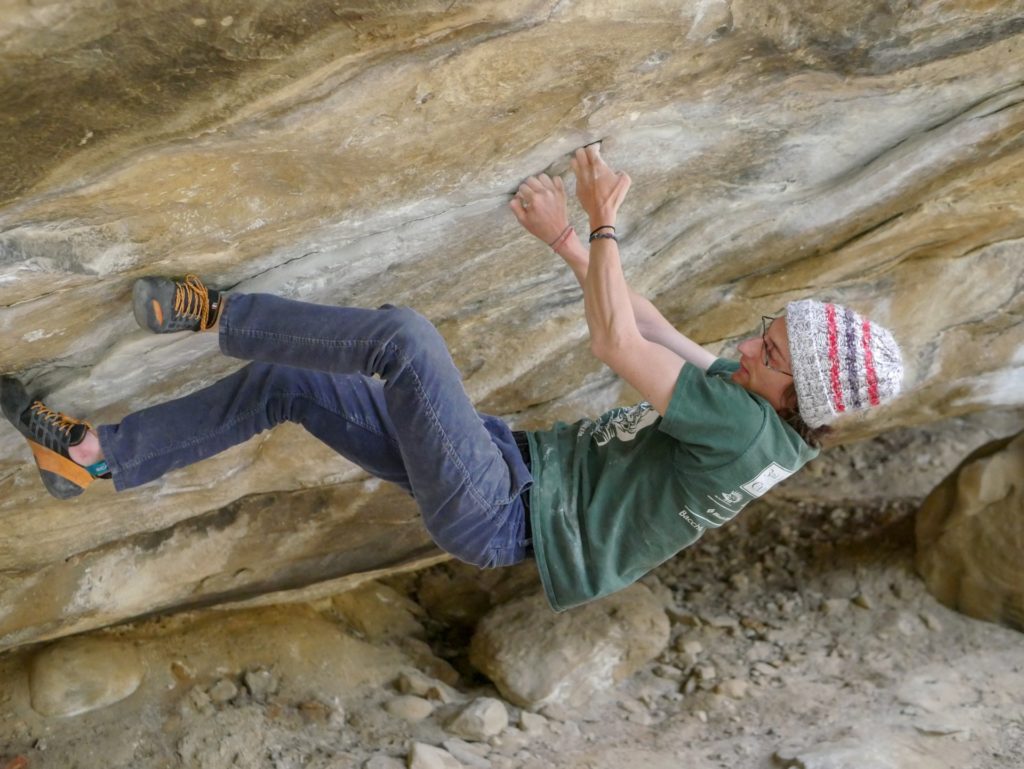

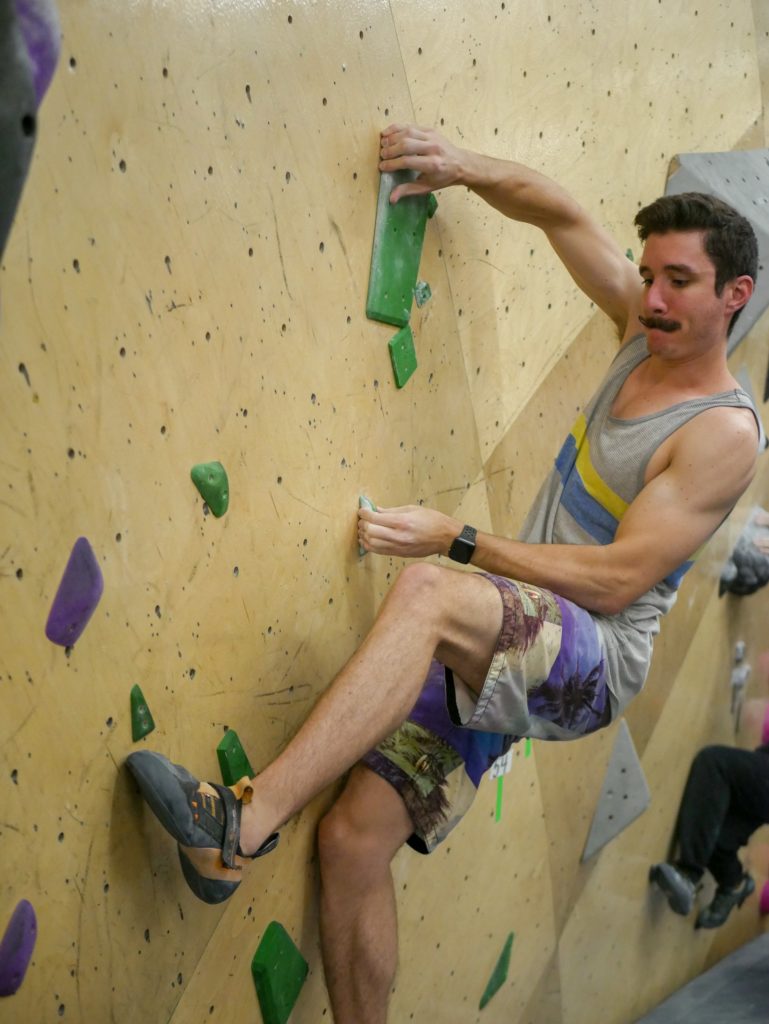

An analysis on rock climbing

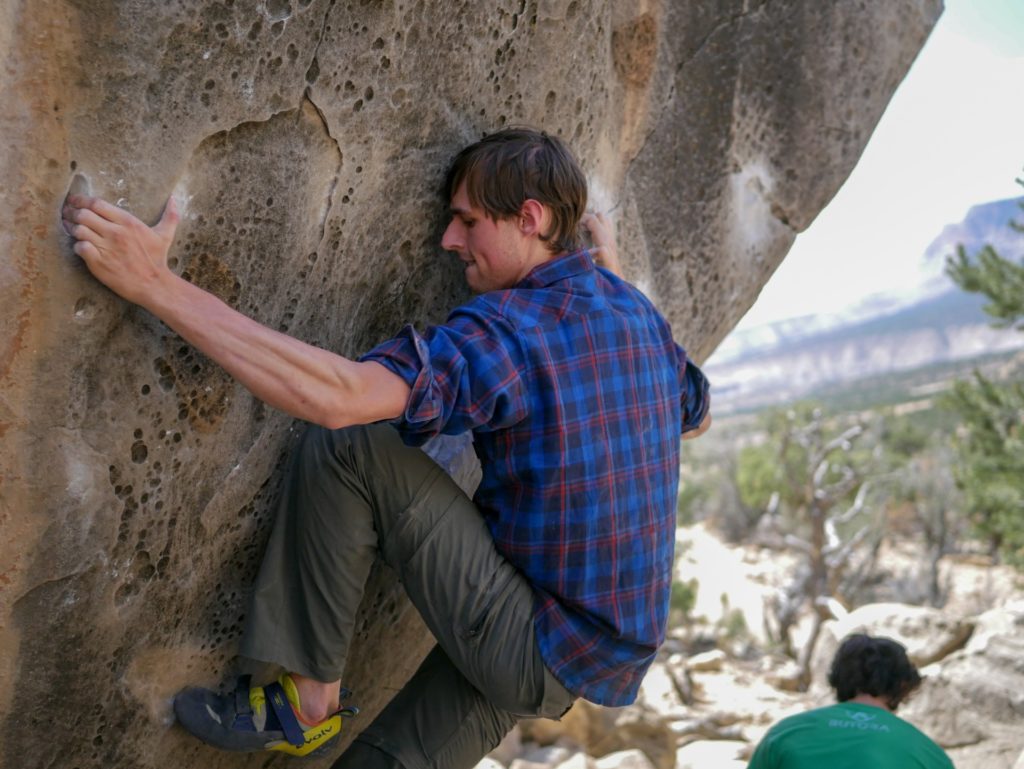

Rock climbing is becoming increasingly popular, with climbing officially approved for the 2020 Olympics, inevitably this sport with continue to grow. Let’s apply The Hobbyists Guide to Longevity to rock climbing and begin to analyze what we can do to maximize our performance and continue to progress and climb strong for as long as possible. Everything that follows is intended to help guide your climbing goals to your maximum potential. Many of these concepts can be added into existing programs a climber might be going through as well as hybridized or incorporated in different ways. Adding several corrective exercises to a hangboard program such as the BeastMaker, for instance, is just one way to incorporate these strategies. Exercises can be implemented as warm-ups or cooldowns, on dedicated days, or off days, and don’t have to fatigue you or over-train you in conjunction with a packed climbing schedule.

Step 1: Learn the muscles being used in your activity.

Step 2: Determine if any weakness or imbalances currently exist

Step 3: Figure out what Corrective Exercises to implement

Step 4: Construct a program using corrective exercise additives

Step 5: Reassess regularly. Maintain

Step 1: Learn the muscles being used in your activity

Hand/Wrist/Forearm:

Flexor Compartment:

The hand and forearm is a complex structure. Several muscles will act to flex the wrist, as well as deviate to the right and left. Rock climbers are constantly gripping and pinching and that grip strength will develop as your flexors adapt and grow. Because climbing holds vary and climbing is so dynamic, we are always using the flexors and complementary muscles that adduct and abduct the hand. Different muscles are utilized depending on the position of the fingers as well. Some of your flexors close your hand and directly impact your grip strength. Training these muscles should include exercises for the fingers as well as the wrist. Hangboard training, grip implements, campus training all develop these muscles.

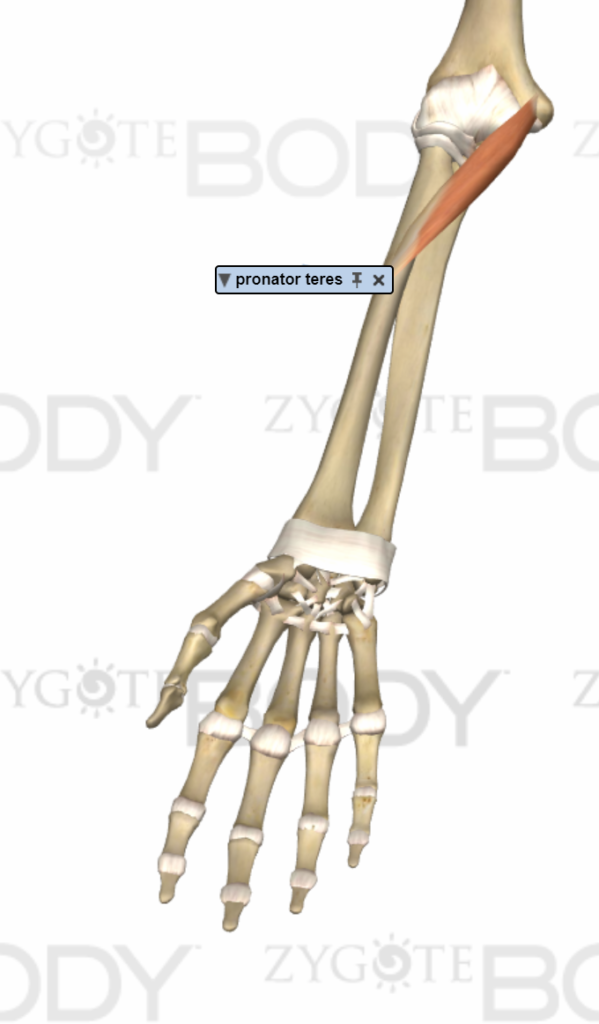

Pronator:

This muscle is used to pronate the hand, turning it over. Logically, your palm is almost always facing the wall when you go to grip a hold. This muscle works along with the brachioradialis and brachialis. Many of the corrective exercises address muscles that perform similar functions simultaneously

Upper arm:

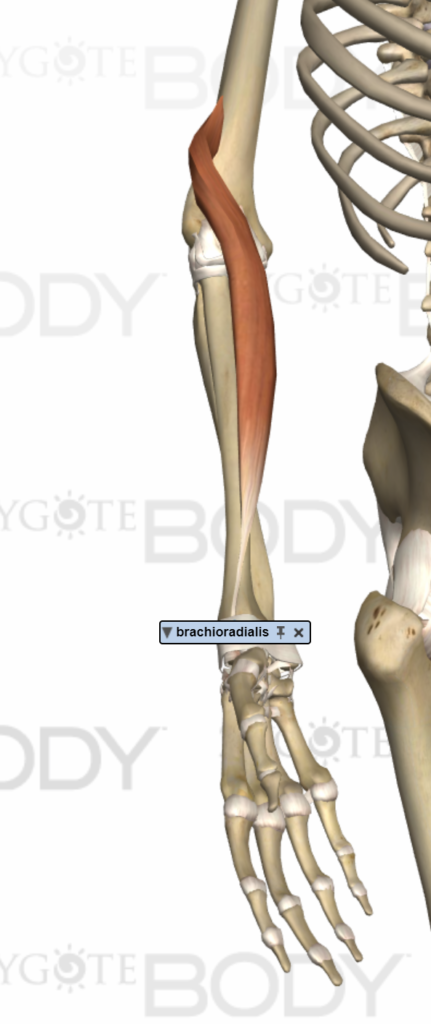

Brachioradialis:

This muscle is the meat of climbing, it’s a strong elbow flexor when the hand is in a neutral position or pronated, which are the most common ways climbers grip holds and pull up. As you Gaston, lock off or move through hold the brachialis is often elicited. Curls in a neutral grip, the pronated grip will target this muscle, as well as pull-ups. The brachioradialis synergizes with the pronator and brachialis so exercises overlap.

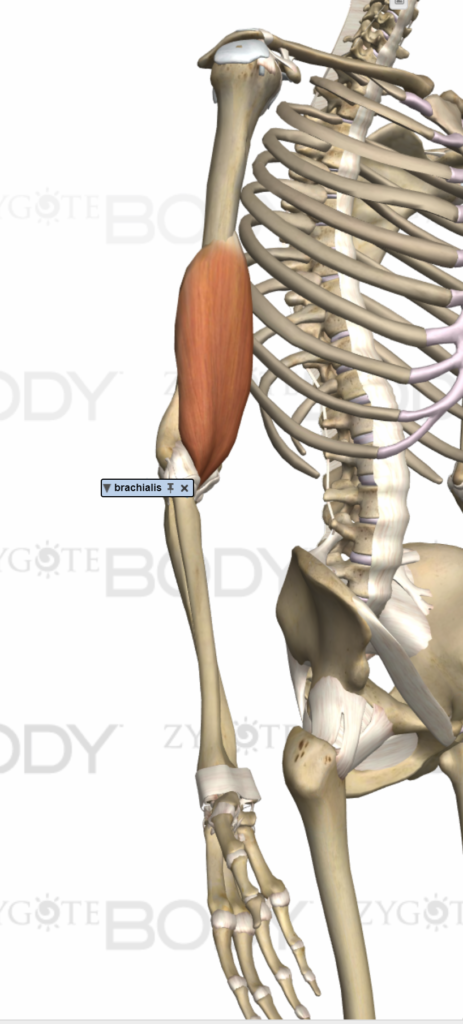

Brachialis:

This muscle acts with the brachioradialis as the primary elbow flexor when the hand is in a neutral position. Many positions while climbing utilize the Brachioradialis and brachialis synergistically and these two muscles tend to become overdeveloped together. Neutral grip curls and pull-ups will target this muscle. This is the muscle under the bicep and it tends to overdevelop from climbing.

Shoulder:

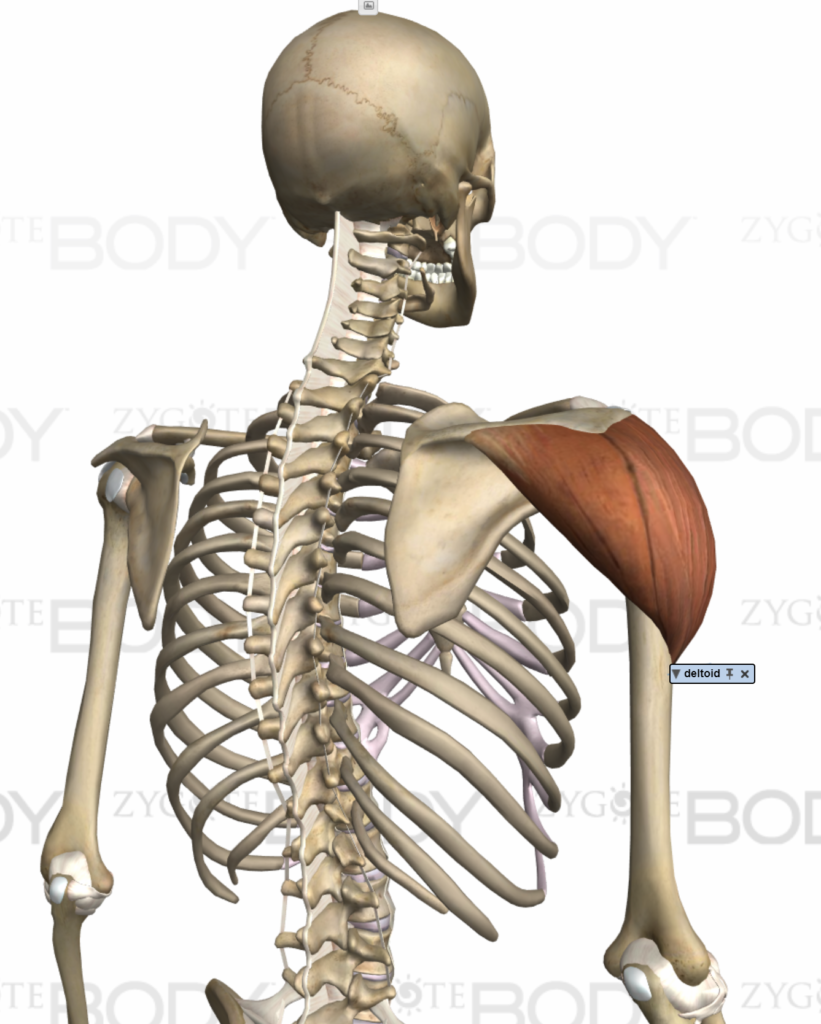

Rear Delt:

Most lock off positions in climbing are going to use the rear delt and rotator cuff muscles. Pulling your body back into the wall with a pinch or undercling is common in climbing. Many times you must extend your body away from a hold, requiring strong shoulders similar to gymnastics!

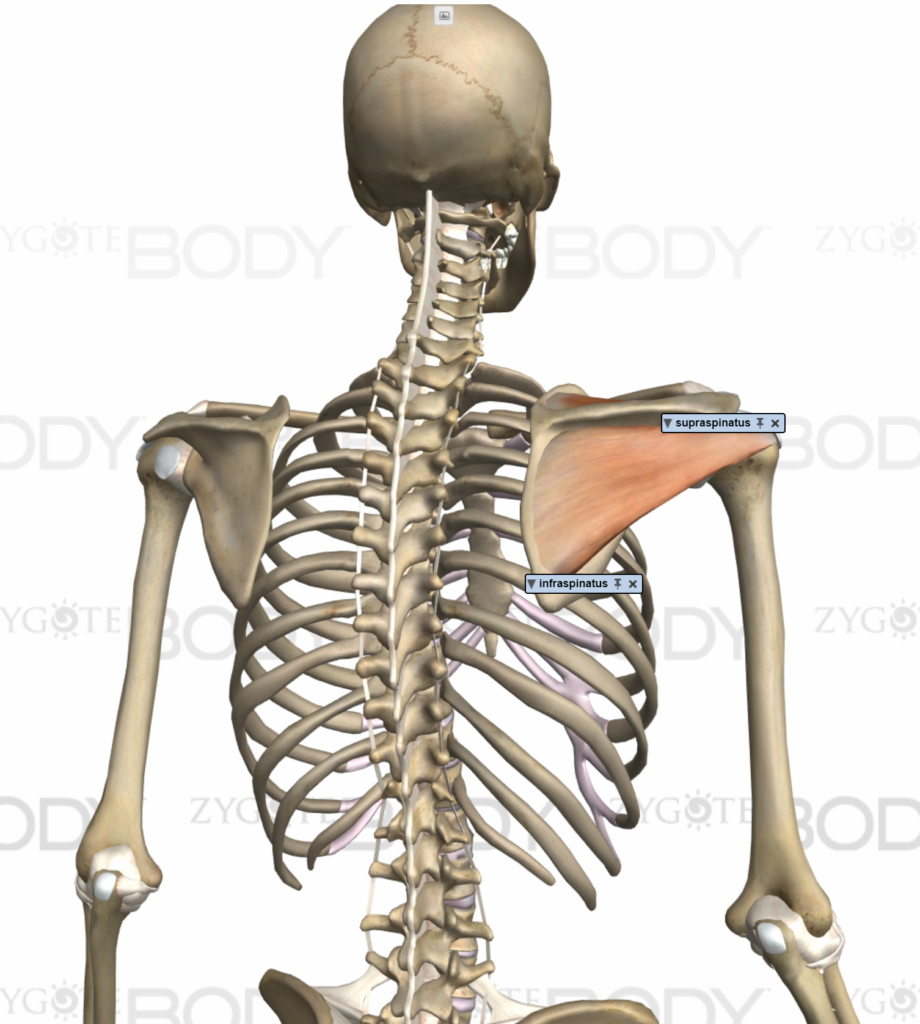

Rotator cuff Muscles:

The rotator cuff is comprised of several muscles. The muscles that we utilize more in climbing are the supraspinatus and infraspinatus. Primarily the external rotators and elevators are overdeveloped. Climbers elicit these muscles to maintain contact with the wall and lock off. Rotator cuff injuries are very common in many sports and life in general. It’s always important to acknowledge these muscles and implement proper exercise to keep them healthy and strong.

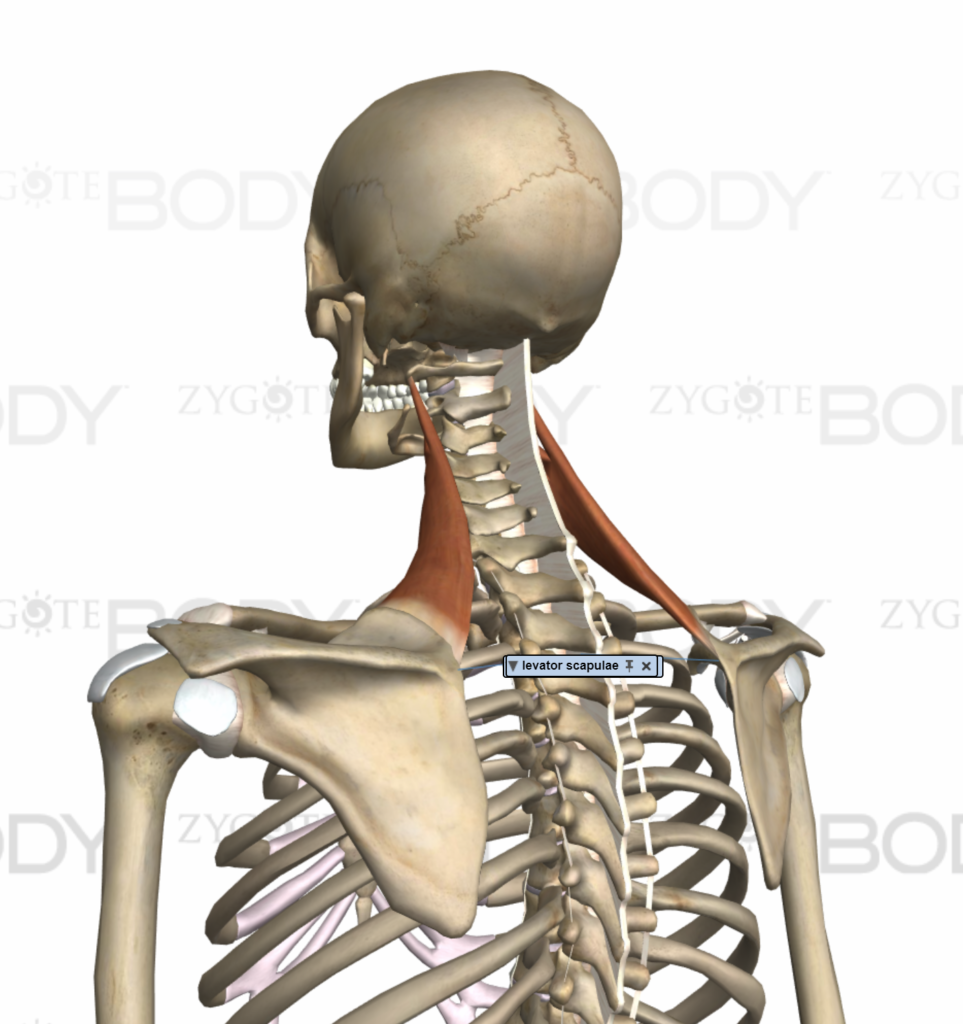

Levator Scapulae:

This posterior neck muscle is often a culprit in neck pain, forward head posture, upper crossed syndrome, and other upper body and head dysfunctions. Reaching for holds and extended lock off positions over-utilize this muscle. This muscle elevates the scapula and has a tendency to develop trigger points. Releasing this muscle can help reduce many shoulder blade dysfunctions and restore mobility.

Back:

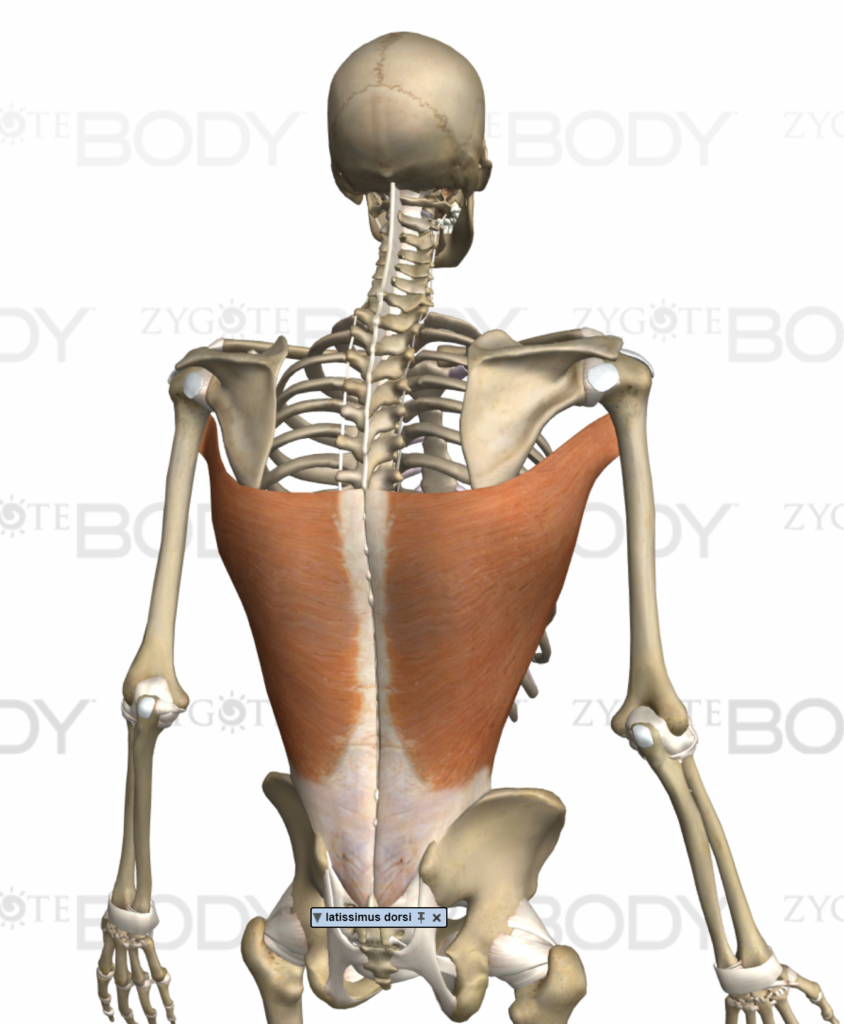

Latissimus Dorsi:

This is a big one, this will adduct the arm back down to the body and is used every time we pull on a hold. This is the muscle that you use during a pull-up. Almost anyone entering rock climbing who has a base level of strength of lifting experience will pull their way through problems. Muscling yourself through a problem is almost all on your lats and hand strength. The lats are huge, and a contributor to many postural imbalances. It is very important to address the lats in regards to spine flexibility and strength.

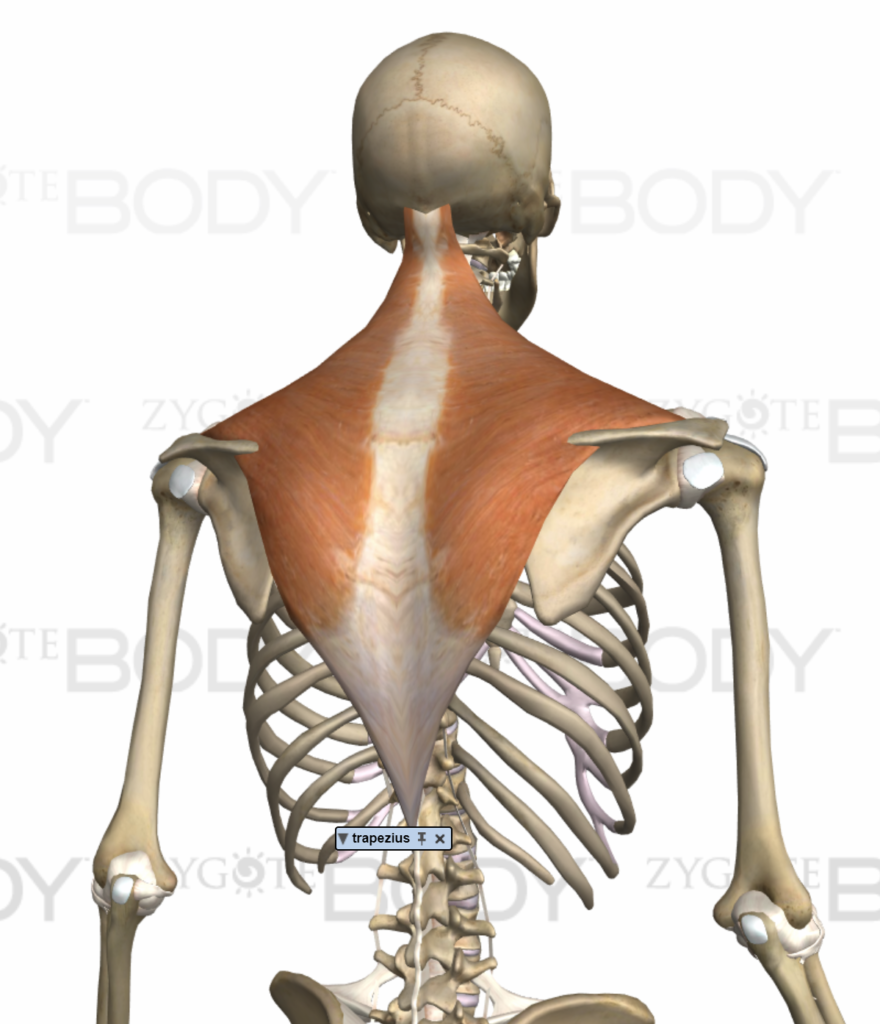

Trapezius:

This muscle is used in many lock off and hanging positions and is generally engaged. The lower traps retract and depresses your shoulder blades. These muscles should work synergistically with the lats and depending on how lat-dominate the climber is, the lower traps might be overdeveloped or the opposite, inhibited! This is why it’s important to assess these back muscles with something like a Standard Pull and Push Assessment

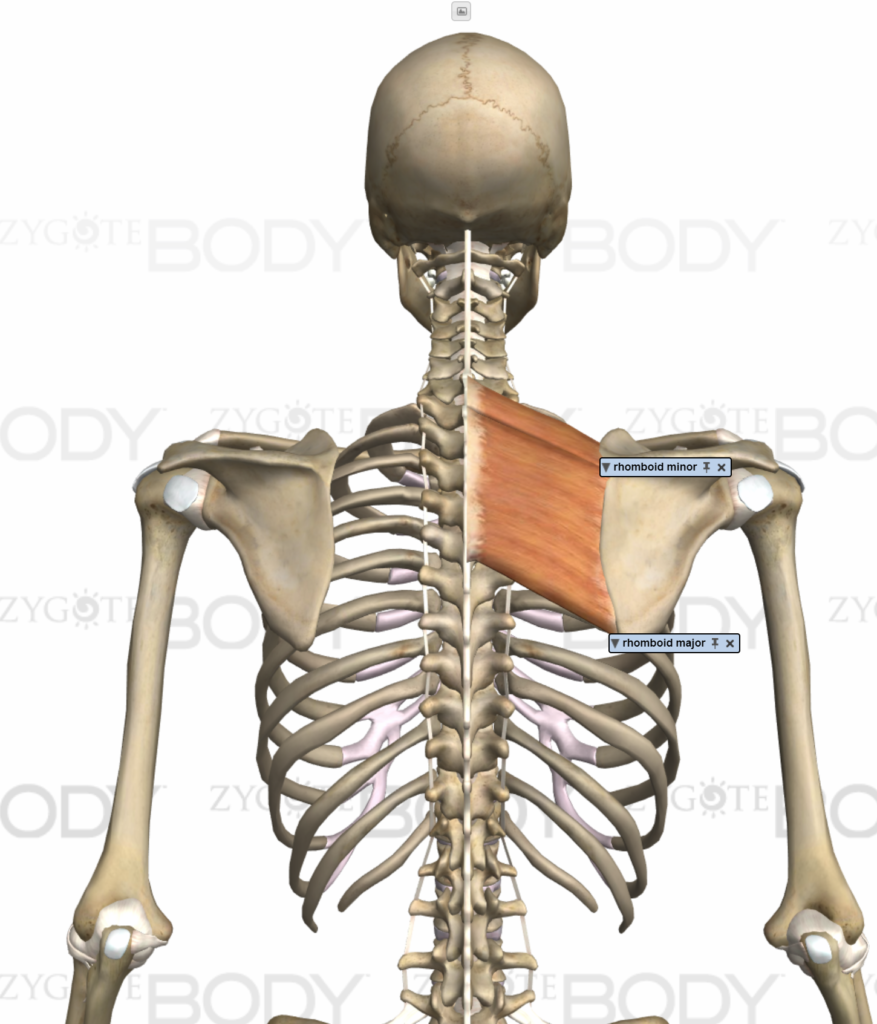

Rhomboids:

Many lock off and rest positions elicit these muscles, they keep your shoulder blades pulled into your spine. These muscles should work synergistically with your traps and also might be affected by how lat dominate the climber is. Sometimes climbers move very relaxed and don’t focus on shoulder blade retraction. These climbers might have their Rhomboids and lower traps inhibited and weak! Once again this is why it’s important to perform an assessment or consult a professional.

Core and Leg Musculature:

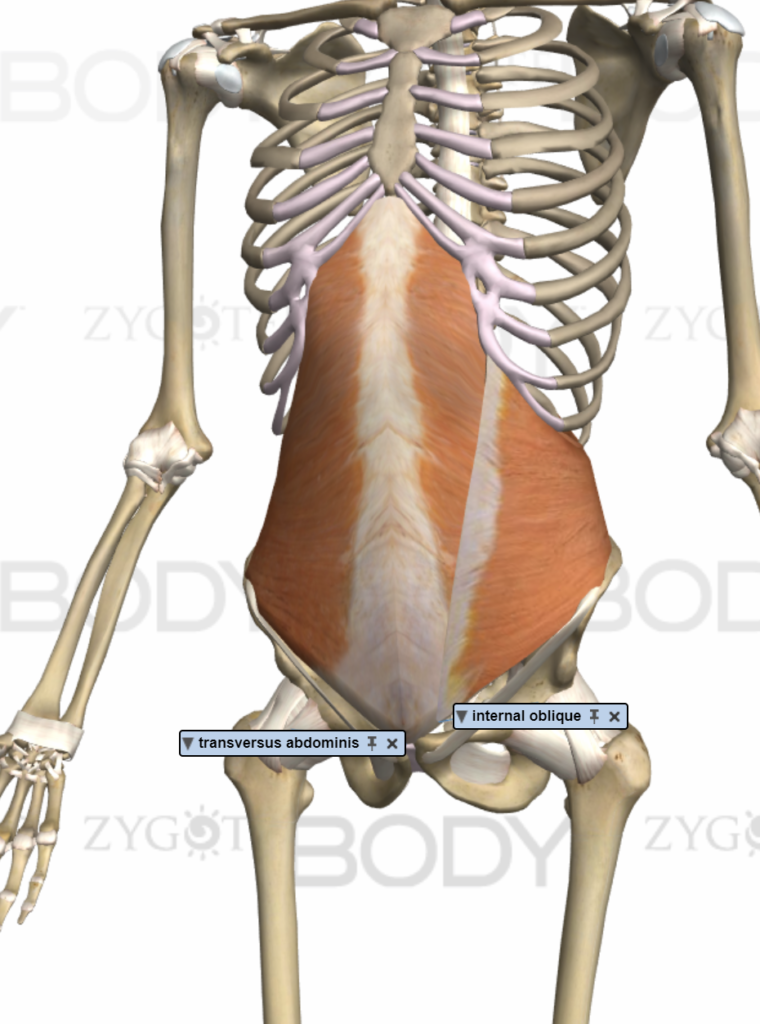

Inner abdominal muscles:

There are many muscles that comprise the core. Many people are confused by what the Core actually is. Check out this post on the CORE. The core muscles will help to stabilize your body through dynamic movements. Maintaining control when cutting feet or moving through a roof requires very strong core muscles. Tiny slab and balance problems where you must remain close to the wall all require a strong core.

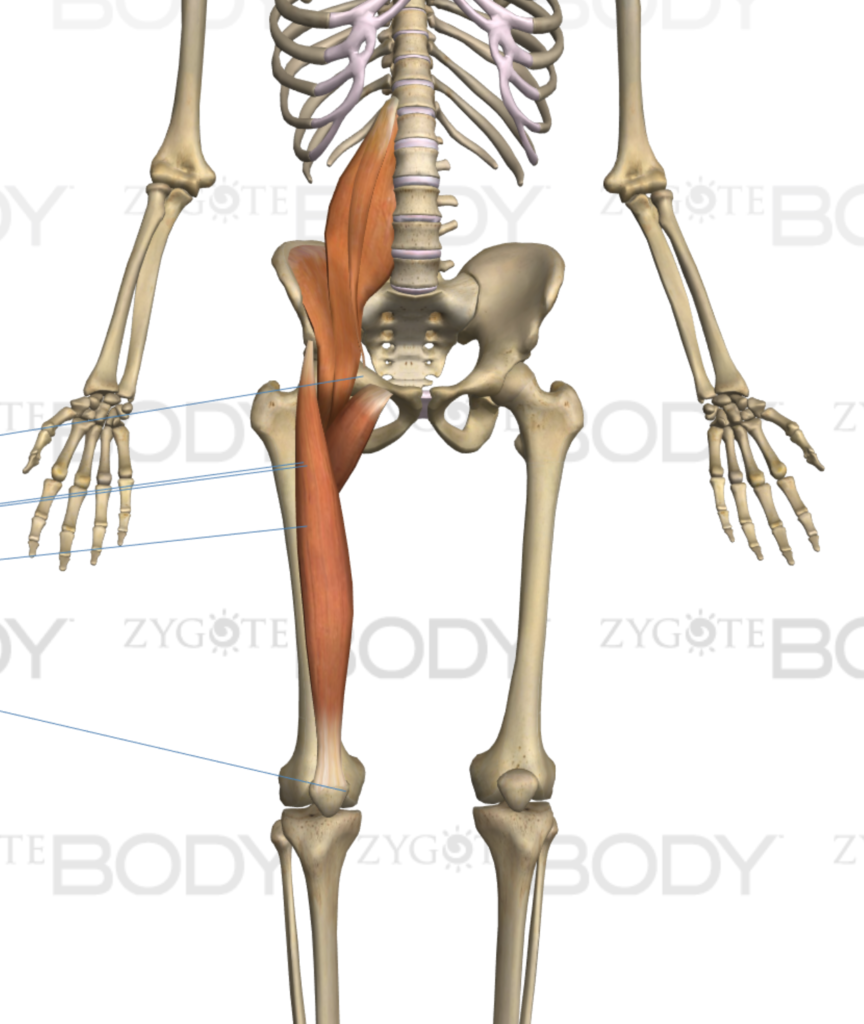

Hip Flexors:

High feet and strange positions often elicit the use of these muscles. Climbers need to generate foot tension and force from very extended or disadvantageous positions. Especially boulderers. Roof climbing, stemming on weird off-widths, and chimneys all stress your hips and legs to the max! Making sure all of the small stabilizer muscles surrounding the hip and ankle is very important.

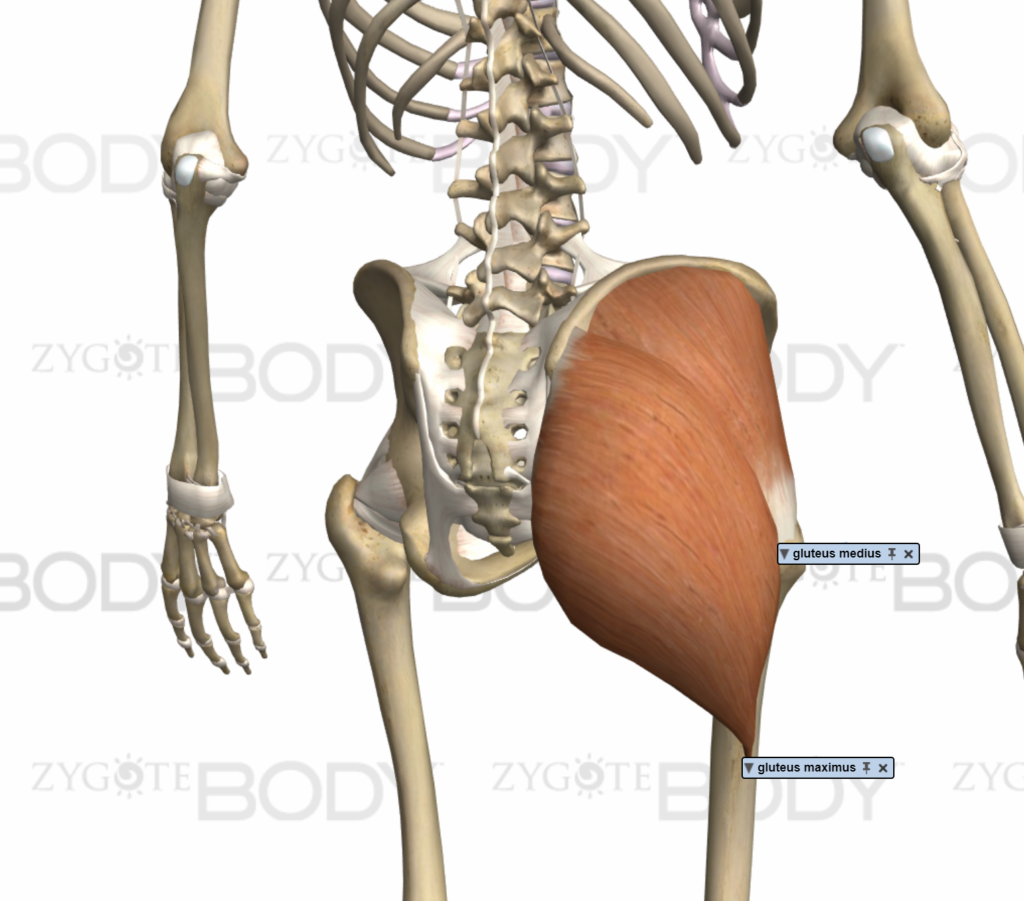

Glutes:

Climbing utilizes your glutes every time you push off of a hold and continue upward! The glutes are a tremendously important muscle. Often inhibited, they are the target of many corrective exercise programs throughout many sports and even for overall health. Making sure the glutes are strong and functional is important to a strong stable core and being able to keep yourself into the wall during even the most cramped and overhanging problems.

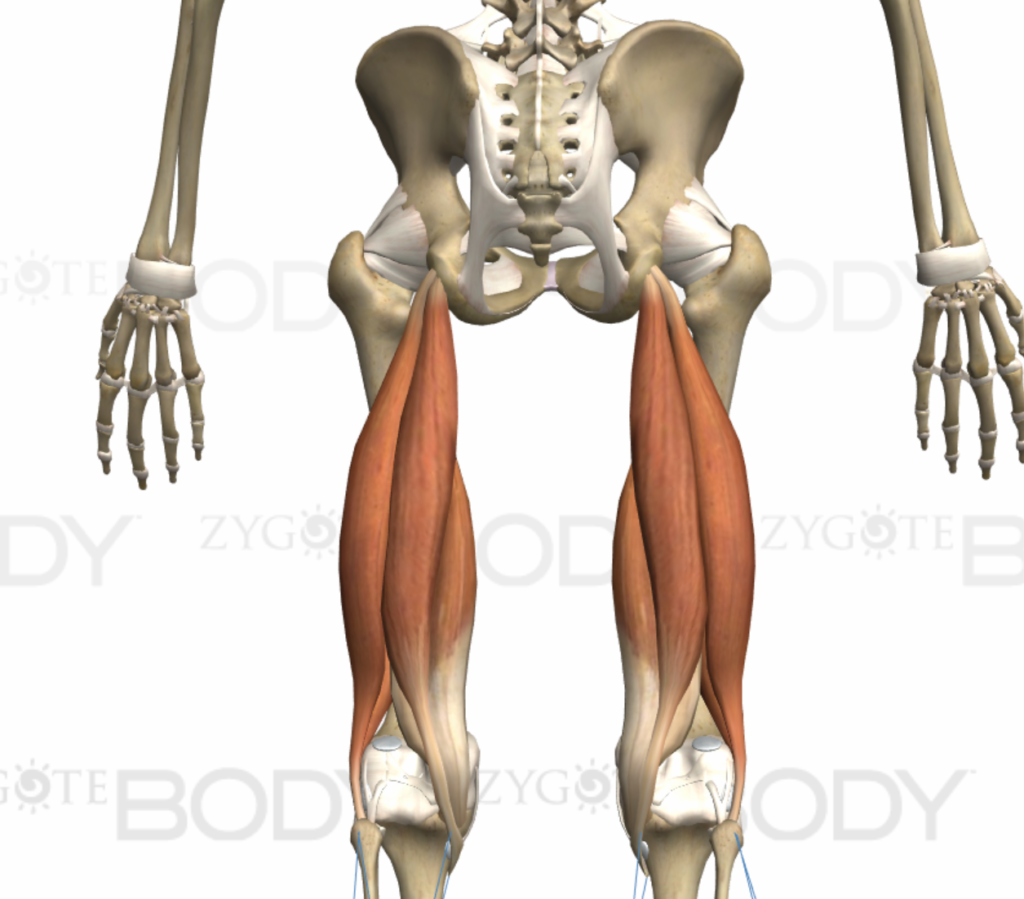

Hamstrings:

Heel hooks, rest positions, and body tension moves often require a climber to pull in with his feet. Having mobile hamstrings that are strong and capable in strange positions are important to avoid strains, cramps, and injury! Many times I’ve seen climbers cramp out in their hamstrings or calves during hard heel hook leg tension moves. The shoes don’t help!

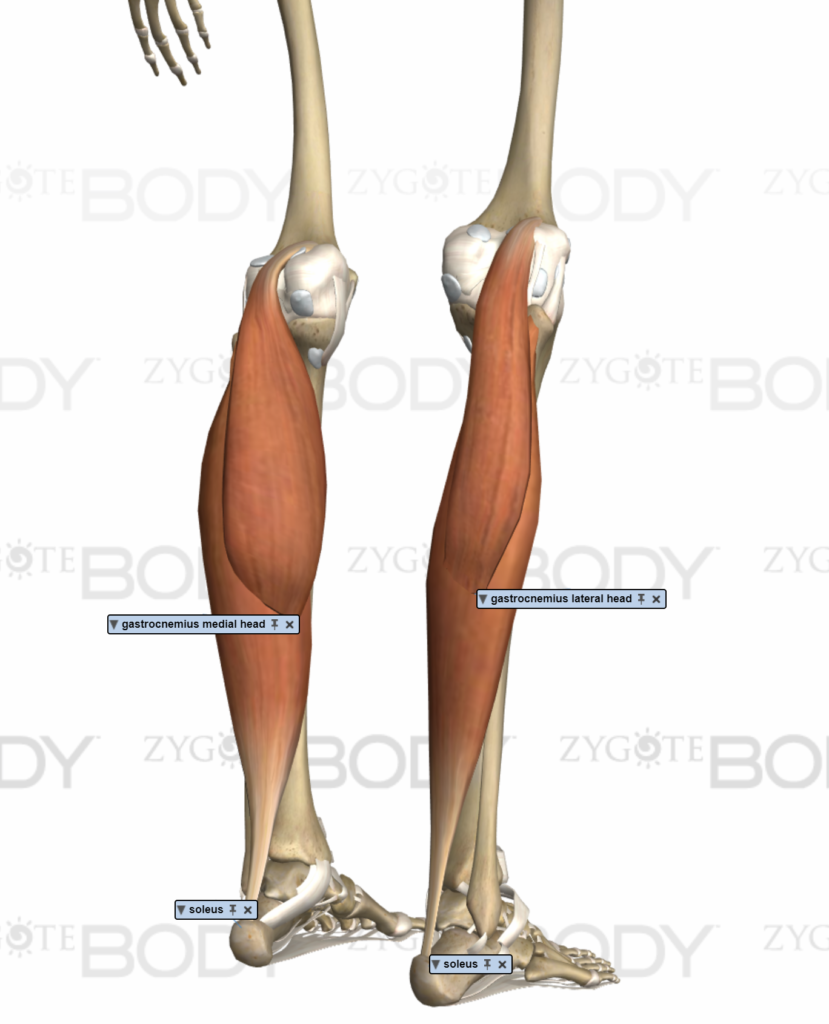

Calves:

Small foot chips, slab and general climbing all utilize these muscles. Most of the moves that would tax your hamstrings would also tax your calves. During long sport or trad routes often you are on your toes and having strong and conditioned calves are essential for making it through. Another thing many people don’t think about is ankle stability. I’ve seen many twisted and messed up ankles from just jumping off a bouldering problem or falling in a weird way. Strengthening the calves and ankle can help to strengthen your body for these kinds of accidents. You’ll also be happy to have strong ankles during long approaches and hikes.

Step 2: Determine if any weakness or imbalances currently exist

Muscle imbalances tend to be the root of many problems when it comes to performance. As we know from Previous Posts, it is important to address these imbalances. We must determine what imbalances your activity might induce. Generally, muscles that are overused in activity have an opposite muscle that is weakened or inhibited. There are many Assessments that you can perform to determine what they are.

It is important to make sure that all the primary muscles in climbing are balanced, that no muscle groups are dominating over a movement or function. Making sure muscles work synergistically is how you can be as strong as possible.

The big thing about climbing is assessing the function of your hand and elbow. Making sure you have similar strength in extension and flexion, abduction and adduction, supination and pronation. The therarods are an excellent tool to assess muscle imbalances in the hand wrist and forearm.

Taking note in weakness or inability to complete a decent set of a therarod corrective exercise is important for understanding what strengthening exercises to include or avoid.

There are also muscle groups that almost get no work in climbing. It’s essential to acknowledge these muscles and train them so they don’t contribute to overall imbalances, posture problems, previous injuries, and future injuries. For all the muscles we talked about that should be utilized in climbing, there are opposite muscles that could be neglected and dysfunctional. Strengthening these muscles is a necessary step to the entire process.

Let’s take a look at commonly weakened or neglected muscles in rock climbers:

Hand/Wrist/Forearm:

Extensors:

While the wrist extensors tend to be strong in climbers, the finger/hand extensors are not! Often well see weakness opening particular fingers or the hand in various positions. These muscles are often inhibited and weakened from constantly fighting against all the muscles you use to grip and move around the wall. Rice bucket, rubber band around the fingers are all strategies to strengthen these muscle groups.

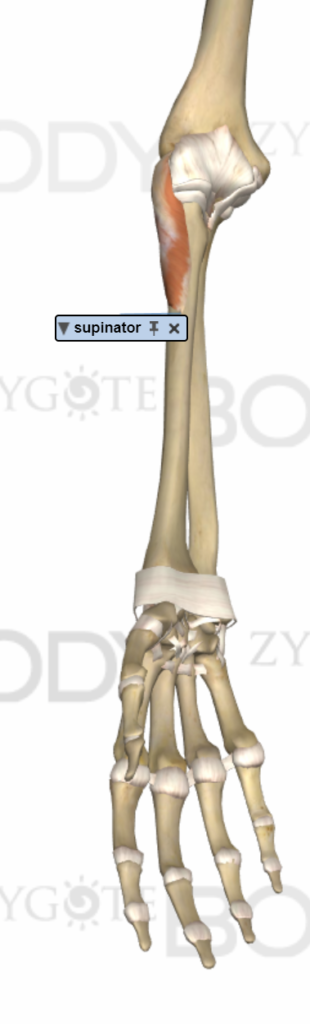

Supinator:

It’s not often that we are holding onto a hold from a fully supinated position, although it does happen. Because most climbing positions place the hand in a pronated or neutral position, the supinator and bicep often become inhibited to favor the use of the brachioradialis and the brachialis. This imbalance might lead to elbow pain and imbalances surrounding elbow function.

Upper arm:

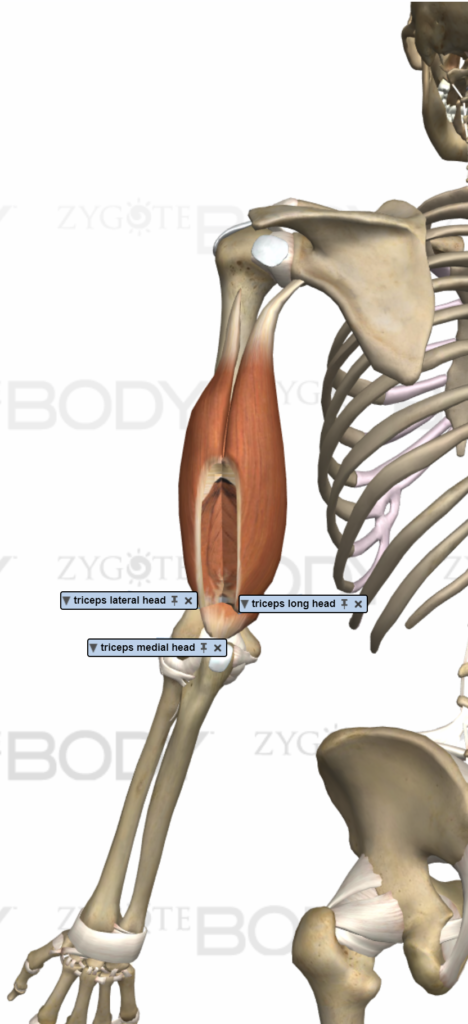

Triceps:

This essential muscle group balances the elbow. Your triceps extend the elbow and assist slightly in extending the arm as well. Your triceps synergize with the chest and assist in pushing you or an object away from the body. The triceps are antagonists to your elbow flexors, so essentially these are the muscles you need to keep strong to counteract the overdeveloped climbing muscles.

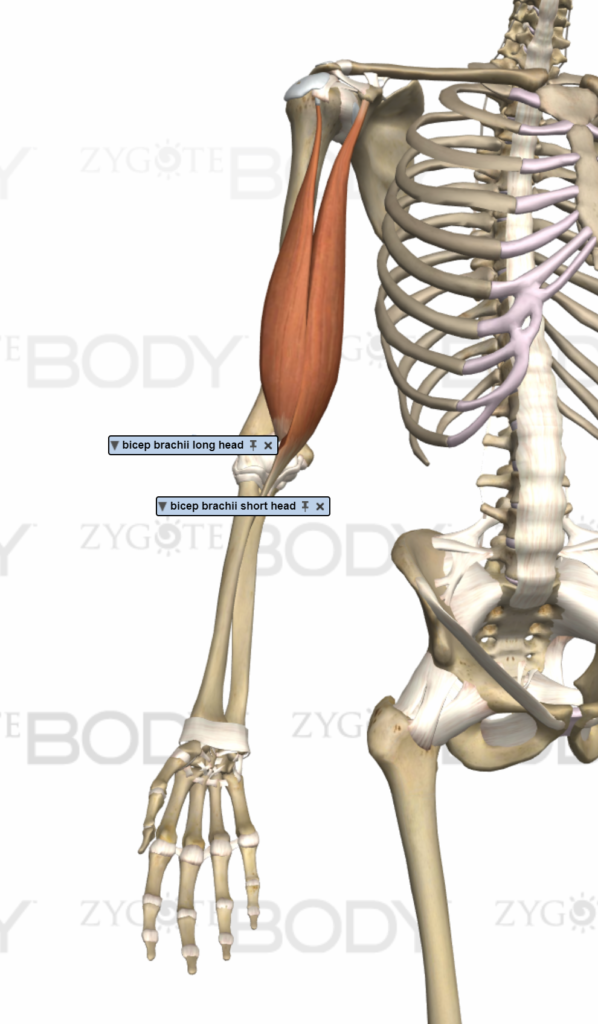

Biceps:

The biceps and supinator work synergistically to turn the palm out. This isn’t a very common rock climbing position, and therefore these important muscles often develop dysfunction. Making sure the bicep and supinator are strong and developed alongside the brachialis and brachioradialis will not only create an aesthetically pleasing arm but also a healthier one hopefully free of pain!

Shoulder:

Front Delt:

This muscle synergizes with your chest to lift objects in front of the body. This muscle tends to become weakened in rock climbers, as its antagonist, the rear delt, tends to become overdeveloped from overuse. If the front and rear delts aren’t balanced properly, injury risk increases dramatically as the function of your entire shoulder joint becomes compromised.

Trunk:

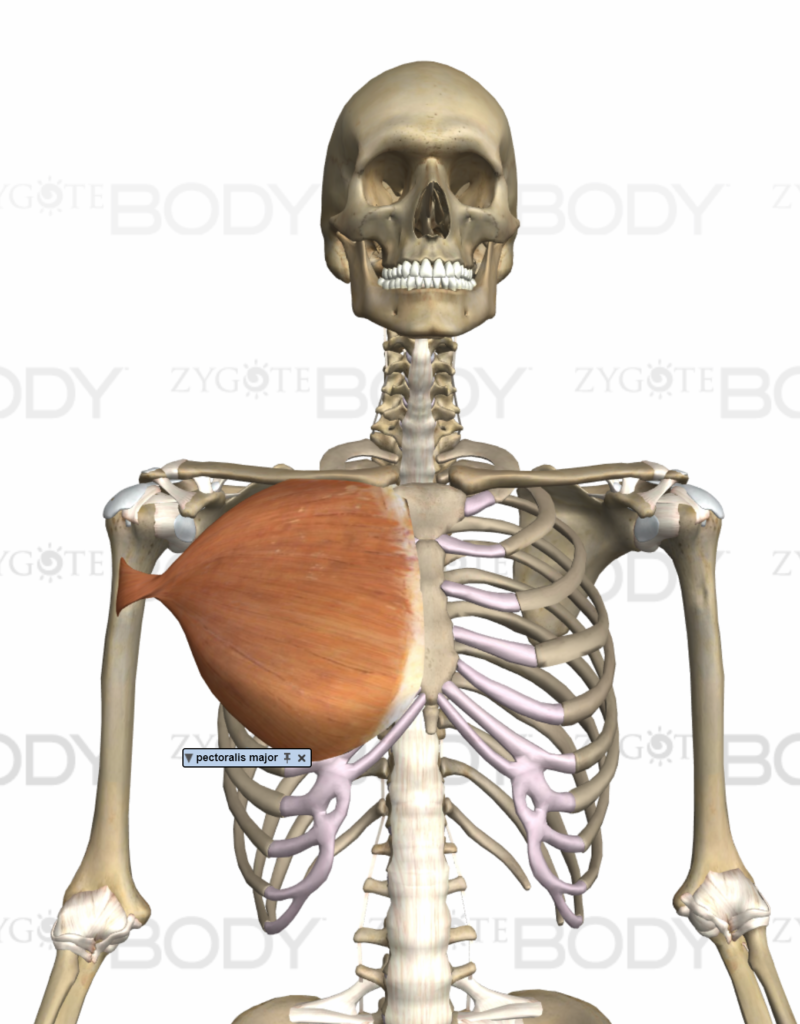

Pec Major:

This massive muscle synergizes with your triceps and front delts to push you away from an object, or an object away from you. Your pec draws your arm across your body. The pec is the antagonist of your lats and many back muscles, and therefore it’s essential to keep it strong to maintain a balanced thoracic spine. When you see a climber posture begin to develop, the shoulders and upper back round forward and you can bet that the pec has become weak and inhibited!

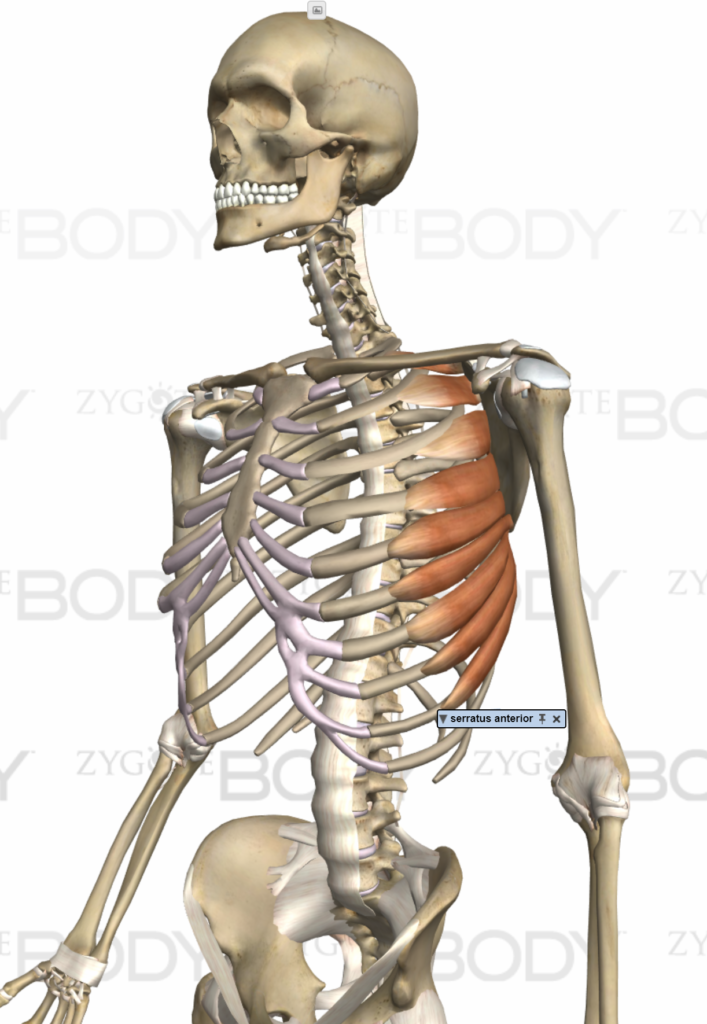

Serratus anterior:

These are the small teeth looking muscles under your chest above your abs. This muscle is very important for keeping your shoulder blade stable through arm motions overhead, in front, and across the body. This muscle tends to become inhibited and dysfunctional alongside the pec and other thoracic muscles.

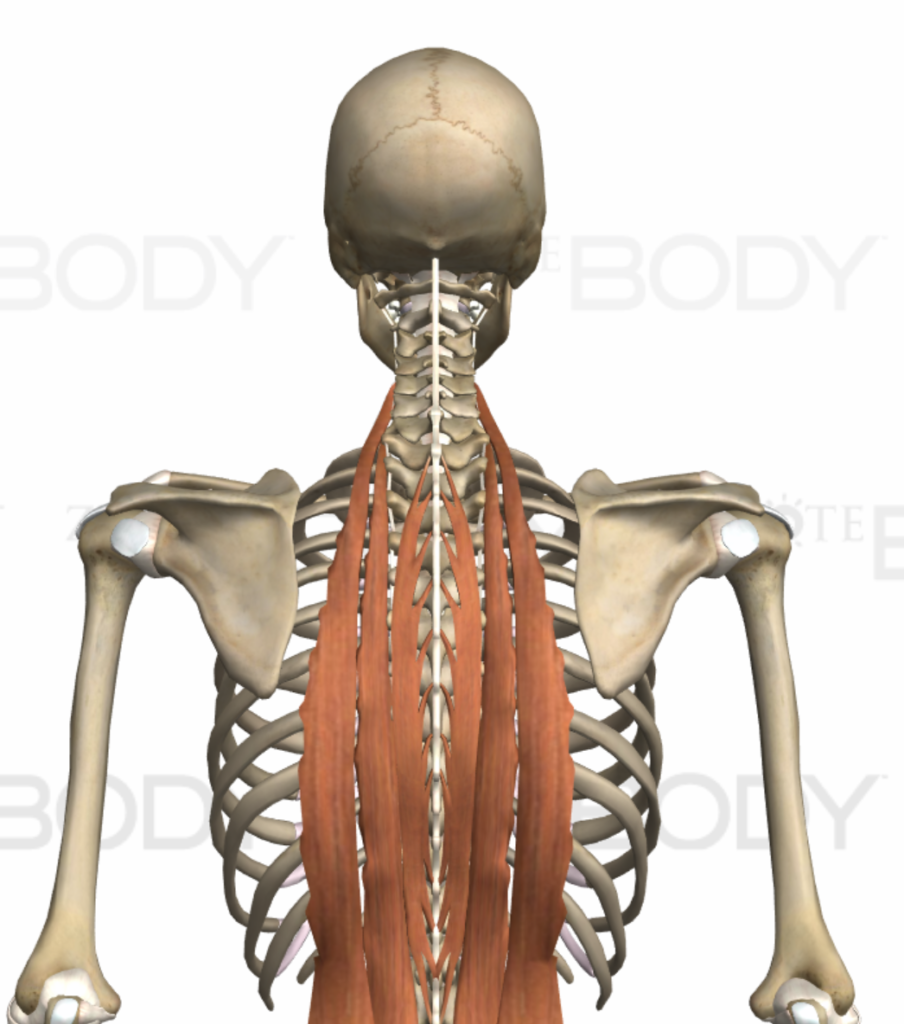

Thoracic extensors:

These are the muscles along your spine that help to straighten and extend your mid back, or thoracic spine. When you see a climber hunched over and rounded forward, these muscles tend to be dysfunctional and weakened. Making sure an athlete has thoracic mobility is essential. It improves performance from so many levels, including breathing.

Step 3: Figure out what Corrective Exercises to implement

Now that we have a better idea of the muscles we are overusing, and the muscles we might be neglecting, we can begin to take action. After performing an assessment to confirm certain muscles are weak we can incorporate strengthening exercises in our programs for that muscle. We can target our overdeveloped muscles with mobility techniques like foam rolling and other release strategies, stretching etc. Release techniques could be most beneficial when utilized between sets of resistance exercise. For example, releasing your hamstrings between your deadlift sets might get you into a better starting position to generate more force and recruit your glutes easier.

It’s important to understand these exercises are meant to strengthen a climber and not fatigue them or take away from their project. When added in systematically to a program, all of the supplemental exercises should allow a climber to climb often and continue to try hard projects. Adding or removing the volume of resistance exercise will help prevent overtraining and too much fatigue on the wall. Programming is very important and is what will account for your projects and still being able to incorporate corrective exercise and body maintenance. Programming is discussed in the next step.

Let’s say we have a climber who discovers his biceps and supinators are weak along with his chest and front delt. He or she ran through several assessments, some exercises and discovered a weakness. Now we want to pick corrective exercises to strengthen the chest and shoulders, and the biceps and incorporate them into our programming. These are additives to a program and should be focused on constantly in conjunction with your training phases. A boulderer will incorporate minor corrective exercises for the chest and biceps in their warm up, and maybe a day of strengthening for those weakened muscle groups during a low-intensity climbing day, a phase 1 day. For instance, during a phase one day, a climber might climb easy to moderate problems for a session, then have a low to moderate weight resistance training session afterward for these weakened muscle groups. There are many ways to approach this, and this leads to the next step, programming!

Step 4: Construct a program using corrective exercise additives

Programming should always be individualized, centered around the activity and goals of the athlete. This step is the meat and potatoes and should be well thought out. If your goal is long hard sport routes, your programming is going to look much different than short hardcore bouldering problems or cerebral day long trad ascents. Specificity is key and most of your training is going to revolve around the kind of climbing you wish to excel at. The exercises we choose are going to compliment a full schedule of climbing and aid in recovery and continued progress. We want to avoid plateaus and injury at all cost, and cycling your training to incorporate your weakest links will give you the best chance to accomplish that! This is where we add in our corrective exercises and begin to correct muscular imbalances and really bring an athlete to their potential. To program for a rock climber, we need to understand what kind of climber they want to be, what their focus is.

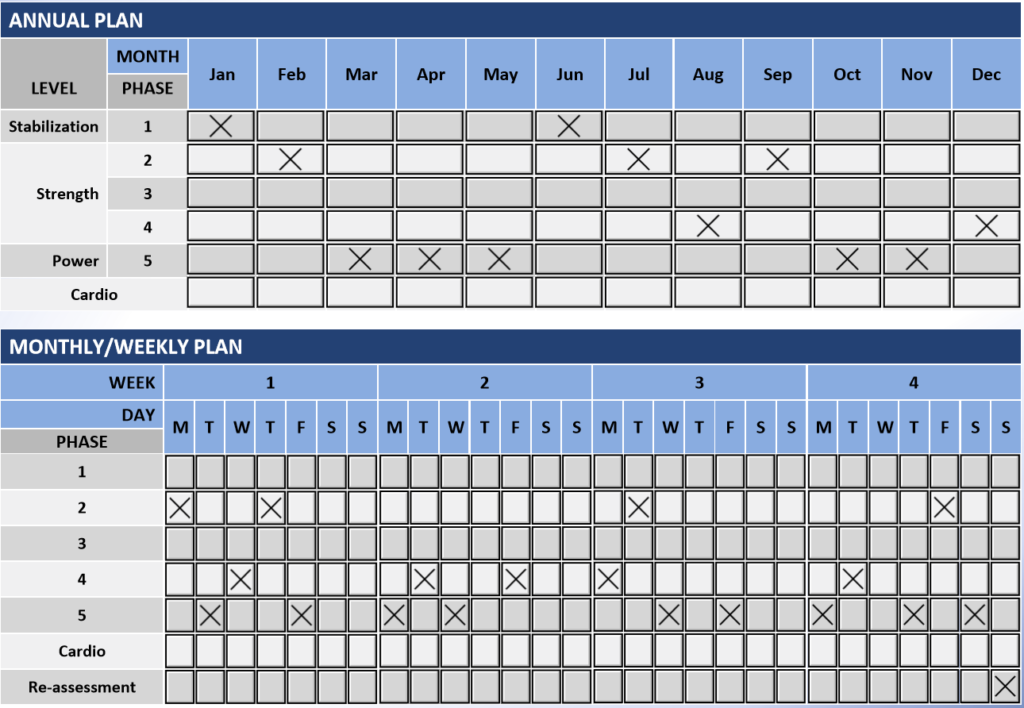

Let’s take a look at 3 basic examples for 3 types of rock climbing programming spanning over one year of training:

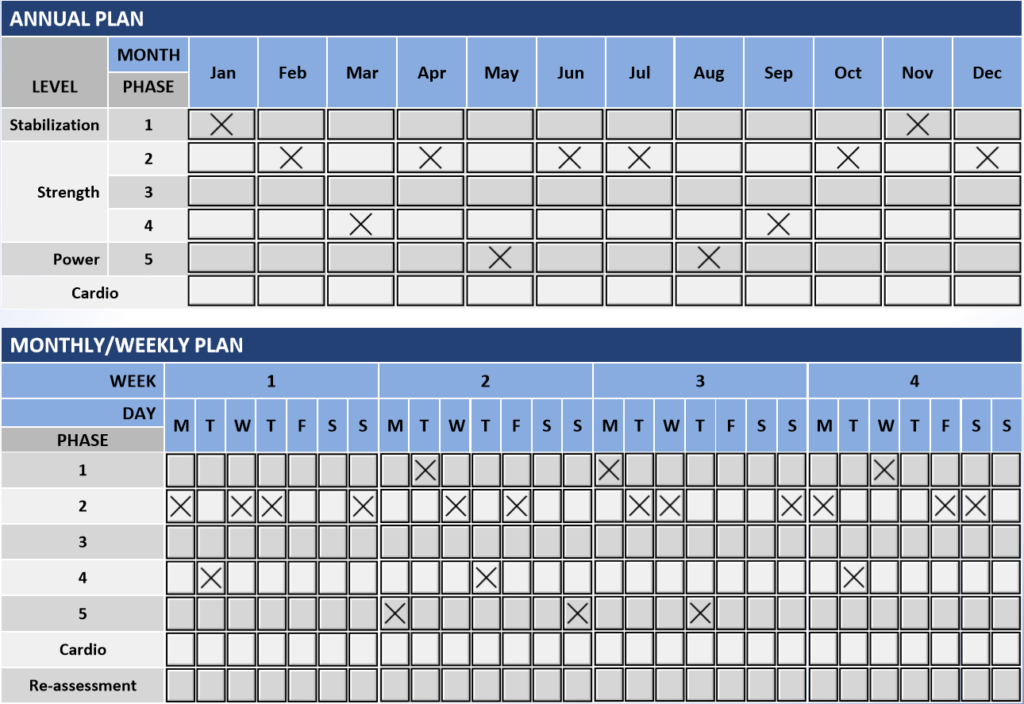

Bouldering periodization:

A boulderer needs to be strong, capable of holding onto the tiniest holds and exerting all of their strength in a short period of time to complete their problem. No doubt power and strength should be the focus of this style of climbing. The problem is the body will break down if you are constantly pushing it at its limits. It is important to cycle through styles of training so you can continue and avoid injury or plateaus. We use periodization to ramp up athletes into performing at their best. We can plan this around events and competitions so the athlete is prepared and at their strongest.

In this example, phase 1 contains balance and coordination based exercises. Single leg balance and progressions, bosu ball exercises, resistance, and reaction training on a stability ball are all the kinds of things the athlete will be doing. These are all done with lightweight and the level of stress on the body is significantly less than power or maximum-strength training. These are good exercises when someone first starts a training program or used as a period of recovery between harder training periods.

The strength phases are strength-endurance, muscle building, and maximum strength. The power phase contains all explosive exercises, plyometrics etc.

Strength endurance is a good way for a boulderer to ramp into or down from their more intense periods of training. This training is more suited to sport climbers. A lot of lengthy endurance climbing, high rep resistance exercise, hangboard repeaters, and campus sets. This is a good period of training to round out an athlete.

Maximum-strength will focus on loaded hangboard sessions and increasing maximum finger and arm strength. This is very intense and therefore focused on briefly when visited, but maintained throughout the year. Constantly climbing and working projects will maintain this at the higher levels of climbing.

Power phases will focus on movement and technique, moonboard sessions, campus training, explosive compound movements. This is the bread and butter for a good boulderer. This style of exercise will keep your joints strong and healthy when making strong big dynamic moves on the wall. We want to peak these skills and strengths surrounding competitions and big projects.

As you can see, the meat and potatoes of what makes a boulderer is what is really focused. We visit other forms of training throughout the year to keep the athlete well rounded and de-load from high-intensity periods of training.

When we break down a day by day plan, we can see that what is being performed undulates as well, addressing the main goal most frequently throughout the week and month, but ramping up and down training phases to avoid overtraining. Let’s look at some other programming strategies for a slightly different climbing goal!

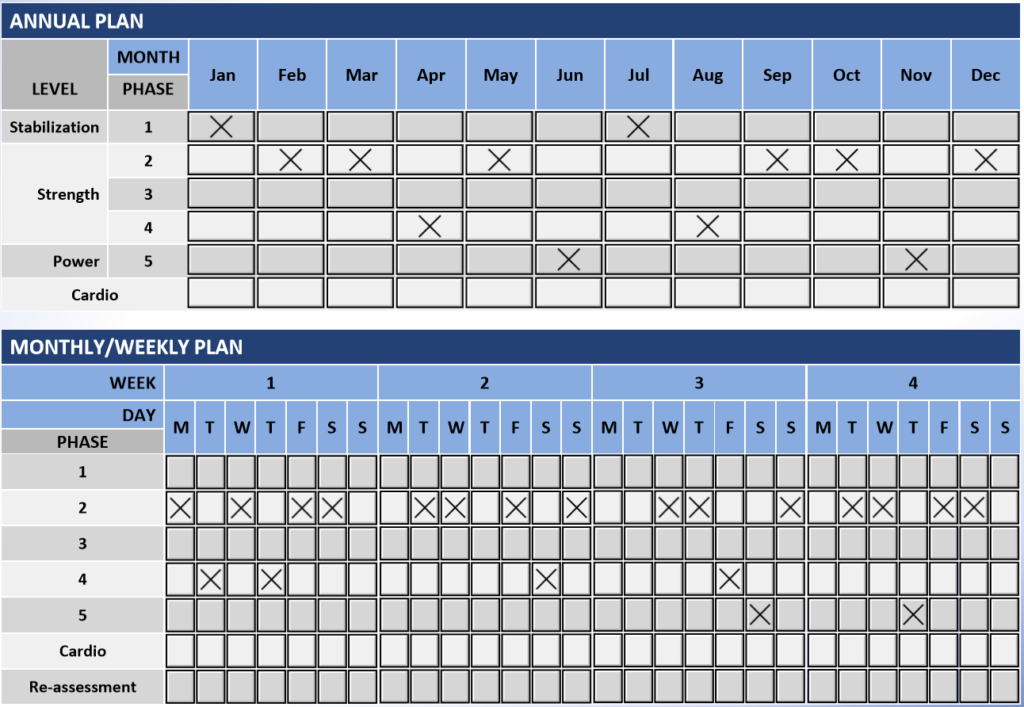

Sport climbing periodization:

Sport climbers need to be tremendously strong in their fingers, but also capable of performing for extended routes with minimal rest. Strength endurance is a sport climbers best friend. Hovering in the strength endurance phase for a sport climber just makes sense. Long sets, sustained exercises, moderate resistance exercises will all help a sport climber push through tricky cruxes on long routes.

A sport climber still needs to be able to perform strong dynamic movements and short-sustained bursts of strength, so including phases of maximum-strength and power will ensure the climber has the capability to go hard if he has to.

As always, the stabilization phase is great for de-loading or ramping up into periods of intense training. Slack-lining is a super popular activity amongst climbers, and also a great thing to practice during this phase! The day to day programming follows a similar strategy as the overall yearly plan and main goal.

Trad climbing periodization:

Trad climbing is heady, as they say. This cerebral form of climbing is mostly sustained, moving through cruxes before stancing out to place gear. This is a well-rounded style of climbing that is physically less demanding than bouldering and sport climbing… generally.

It makes sense for a trad climber to focus a lot on strength-endurance and stabilization, as many of the positions they are in are very balance oriented, and on long multi-pitch routes. A trad climber needs to be able to go all day and still have the energy to make decisions, manage gear, clean up, and often walk back.

The harder climbs will certainly require strong fingers and hands so we visit maximum-strength throughout the year. Power is included but infrequent, as it’s not often lead climbers are bouncing around dynamic trad routes 1500 feet in the air.

Step 5: Reassess regularly. Maintain

This is an often neglected step. Too often people get caught in a cycle of unchanging routine and this is exactly how plateaus happen. The same training unchanging becomes ineffective. Of course, we want to be climbing as often as possible, and changing our supplemental exercises and routines is necessary. Maintenance looks different than correction, and warm-up exercises and overall exercise selection will reflect a more balanced athletic person. A well-balanced athlete will be able to handle more overall volume as well, meaning more harder climbing.